Pillars of Virtue – Perseverance

By Dr. Dan Sturdevant

“If you can keep your head when all about you are losing theirs and blaming it on you, if you can trust yourself when all men doubt you, but make allowance for their doubting too; If you can wait and not be tired by waiting, or being lied about, don’t deal in lies, or being hated, don’t give way to hating, and yet don’t look too good, nor talk too wise

If you can dream – and not make dreams your master; if you can think – and not make thoughts your aim; if you can meet with Triumph and Disaster and treat those two impostors just the same;

If you can bear to hear the truth you’ve spoken twisted by knaves to make a trap for fools, or watch the things you gave your life to, broken, and stoop and build ’em up with worn-out tools

If you can make one heap of all your winnings and risk it on one turn of pitch-and-toss, and lose, and start again at your beginnings and never breathe a word about your loss;

If you can force your heart and nerve and sinew to serve your turn long after they are gone, and so hold on when there is nothing in you except the will which says to them: ‘Hold on!’

If you can talk with crowds and keep your virtue, or walk with Kings – nor lose the common touch, if neither foes nor loving friends can hurt you, if all men count with you, but none too much;

If you can fill the unforgiving minute with sixty seconds’ worth of distance run,

Yours is the Earth and everything that’s in it, and – which is more – you’ll be a Man, my son!”

-“If: A Father’s Advice to His Son” by Rudyard Kipling

Hello Parents, Scholars, Friends, and Optima Family!

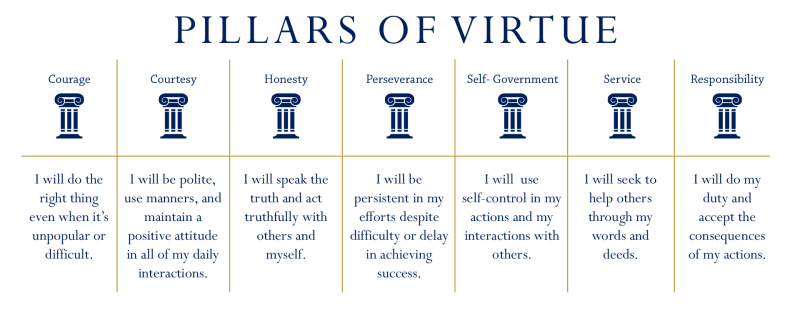

This post will be the fourth in a series of 7, highlighting our 7 pillars of virtue at Optima Classical Academy, and indeed throughout all of our Optima Foundation schools. As you, I am sure, have gathered from the poem above, perseverance is a character trait we are able to discover in many ways – through classic literature and poetry such as “If,” through personal experience and triumph in adversity, and through the example of historical figures and men and women of great resolve. One such example has been in the news quite a bit recently, and is one of my favorite, if not the most well-known, heroic examples from the 20th century.

For those of you who are interested in history, you may have heard recently that Ernest Shackleton’s infamous ship Endurance was recently discovered, almost perfectly preserved in the Antarctic waters where it sank, 107 years ago. Endurance was the base of operations for Shackleton’s expedition attempting to cross Antarctica by sea. However, nearly mid-way through their journey, the ship became trapped in Antarctic sea-ice for several months before being crushed and ultimately sinking. Heroically, Shackleton persevered in the face of unimaginable hardship to not only survive the catastrophic loss of their shelter, transport, and many of their supplies, but also to facilitate the rescue of his crew.

Leading his men away from the wreckage and towards rescue, the crew of the expedition lived on sheet ice, survived a perilous journey across open, frigid ocean waters (in a rowboat!) to an uninhabited island, and then for some, a second journey in an even smaller boat to find a whaler that could come and rescue the crew. Amazingly, not one man of the Endurance crew perished in their 17 month ordeal. While the ship was aptly named for the character of the crew, Shackleton himself, as their leader and captain (“Boss” as he was called onboard) is one of our best modern examples of perseverance.

A contemporary of Shackleton, and a bit of an adventurer himself, Rudyard Kipling published his classic poem “If” only 4 years before the Endurance sailed from London to its ultimate destination. In fact, in a wonderful turn of coincidence, I discovered while researching and writing this blog, after choosing “If” as a frame and Shackleton as a subject, that Shackleton had actually brought a framed copy of the poem with him aboard the Endurance – it hung above his bunk.

So many lines from Kipling’s poem could be applied to Shackleton’s dilemma. I’d imagine his men at times hated him, that they doubted him, and certainly, it is not hard to imagine that many, and likely on several occasions, lost their heads at the prospect of being stranded on the sheet ice for months without the prospect of shelter or sufficient food. However, we know – from both their total survival and from first-hand accounts – that Shackleton kept his head, did not succumb to self-doubt, nor did he turn on his men. Rather, he led his men to safety through unimaginable odds, across dangerous and unpredictable seas, and he held on long after most men’s heart and nerve and sinew would have gone, inspiring his crew to do the same.

“If,” is a wonderful ode to the perseverance we all aspire to, and really it should not be a surprise to us that Shackleton sought out such virtuous instruction and kept it near as he faced a daunting mission. Shackleton could not have known his impending need for such perseverance when he framed that poem above his bunk, but what an excellent lesson for us to prepare our minds with virtuous instruction daily. Indeed, the preparation of Schackleton unknowingly, but virtuously equipped him for the life or death challenge of 17 months of survival on Antarctica. We can’t say what would have happened differently if Shackleton did not have “If” ready for recall, inspiration, and instruction in his mind, but we do know what he was able to do with it accessible to him in those long, cold months; persevere.

This is why we read classic literature, and why we believe in memorization, recitation, and repetition of poetry and great works of oratory. C.S. Lewis wrote “Since it is so likely that (children) will meet cruel enemies, let them at least have heard of brave knights and heroic courage. Otherwise you are making their destiny not brighter but darker.” In that same vein, while our scholars may never meet the same need for perseverance or the same stakes of failure as Ernest Shackleton, they will encounter trying times, and opportunities to quit in the face of adversity. As educators, one of our opportunities, and one of our joys, is to introduce our scholars to virtuous literature and to great men and women, so that when they do encounter hardship, and when they do want to quit, they, like Shackleton have at the ready, inspiration to forge ahead, to persevere, and to put that first and most basic virtue, courage, to use in their act of perseverance.

Thank you for reading, and as always, please reach out to info@optimaclassical.org with your questions and head to our website (www.optimaclassical.org) to register your scholars for our admissions lottery!

Warmly,

Dr. Dan Sturdevant

Head of School